The Friant Water Authority is a public agency that delivers over a million acre-feet of surface water annually to farmers in the Central Valley of California, thus stabilizing the Central Valley’s groundwater supply. The agency represents the interests of water users in the Friant Division of the federal Central Valley Project and operates and maintains the 152-mile-long Friant-Kern Canal. The Friant Division’s other vital infrastructure includes the Friant Dam on Millerton Lake and the 36-mile-long Madera Canal. Operating and maintaining these facilities takes work—and funding. Recently, ground subsidence has begun to severely hamper the functionality of the Friant-Kern Canal, affecting farmers on 330,000 acres of land.

In this interview with Irrigation Leader Editor-in-Chief Kris Polly, Jason Phillips, the chief executive officer of the Friant Water Authority, discusses his agency’s plans for the Friant-Kern Canal and the challenges of securing funding for federal infrastructure in today’s fiscal climate.

Kris Polly: Please tell us about your background and how you ended up in your current position.

Kris Polly: Please tell us about your background and how you ended up in your current position.

Jason Phillips: I grew up in the Willamette Valley of Oregon and graduated with an engineering degree from Portland State University. In 1998, I moved to Sacramento, California, to take a job with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers as a civil engineer and project manager and worked there for a few years on civil works and flood control projects. In 2001, I was offered and took a position at the Bureau of Reclamation in Sacramento, specifically to manage a project to plan a new dam up at Millerton Lake known as Temperance Flat Dam. I took on some additional responsibilities, including dealing with the drainage issue on the west side of the San Joaquin Valley.

I also got involved in the CALFED Bay-Delta Program, which was a systemwide effort to balance California’s water supply, water quality, fishery, and flood control needs. In 2006, still working at Reclamation, I became the program manager of the San Joaquin River Restoration Settlement, an unprecedented attempt to restore an extirpated salmon fishery on the San Joaquin River, from Friant Dam near Fresno all the way to the delta. The salmon fishery had been extinct for 60–70 years because the operation of Friant Dam had dried up the 150 miles of the San Joaquin River below the dam. The San Joaquin River Restoration Program, which had been created as the result of an 18-year lawsuit involving the federal government, Friant contractors, and a coalition of environmental groups, had the goal of trying to restore that salmon fishery. It included over $1 billion of river-restoration work in addition to projects aiming at restoring water to the Friant contractors—the cities, counties, and districts that received water from Millerton Lake.

After 5 years of that, I decided to take on the area manager position for Reclamation’s Klamath Project in Klamath Falls, Oregon. I moved my family there and spent 3 years managing the Klamath Project, a federal irrigation project in Northern California and southern Oregon. Like many water projects in the western United States, the Klamath Project operates at the intersection of agriculture, tribal water rights, and threatened and endangered species. In 2013, we successfully secured a biological opinion from wildlife agencies to allow the Klamath Project to continue operations. At the beginning of 2014, I was selected to be the deputy regional director at Reclamation back in Sacramento and moved my family back. My responsibilities there included oversight of technical departments such as the engineering division, the construction division, planning, and the environmental and permitting departments in Sacramento; I also remained in charge of the Klamath Project.

In 2015, the Friant Water Authority was looking for a chief executive officer and reached out to me. My past assignments, including my work on the proposed Temperance Flat Reservoir project and the San Joaquin River Restoration Program, had helped me develop relationships and build other skills that lent themselves to being CEO. I began in that position at the beginning of 2016.

In 2015, the Friant Water Authority was looking for a chief executive officer and reached out to me. My past assignments, including my work on the proposed Temperance Flat Reservoir project and the San Joaquin River Restoration Program, had helped me develop relationships and build other skills that lent themselves to being CEO. I began in that position at the beginning of 2016.

Kris Polly: Would you tell us about Friant Water Authority and its history?

Jason Phillips: The facilities of the Friant Division were constructed in the early 1900s as part of the larger Central Valley Project. The Central Valley Project includes Shasta Reservoir, Folsom Dam, Friant Dam, and other canals and pumping facilities in Central California. The Friant Division, in particular, was put in place to address groundwater overdraft in the San Joaquin Valley, particularly on the east side, from Madera County, north of Fresno, all the way to Bakersfield, 200 miles to the south. This area boasts some of the most productive agricultural lands in the world, but the groundwater use was unsustainable. Friant Dam was constructed so that in wetter years, farmers could use surface water instead of groundwater and allow the groundwater to recharge. In drier years, they go back to groundwater.

The construction of Friant Dam was completed in 1942 and the overall project came online in 1949. Friant Dam, along with the Madera Canal, which runs 36 miles to the north, and the Friant-Kern Canal, which runs 152 miles to the south, deliver water to about 1.5 million acres of farmland. On a really good year, over 2 million acre-feet of water can be delivered; in drier years, the Friant Division receives 500,000–800,000 acre-feet.

Friant Water Authority is the successor to the Friant Water Users Authority, which in 1986 acquired a contract with the Bureau of Reclamation to operate and maintain the Friant-Kern Canal. Up to this point, Reclamation operated the canal directly, but in the 1980s the federal government made an effort to contract with local entities to operate and maintain federal facilities, and a group of Friant contractors banded together to form an agency to oversee the Friant-Kern Canal. In 2004, the Friant Water Authority was formed to take over the responsibility of maintaining and operating the Friant-Kern Canal. Friant Water Authority is a political subdivision of the State of California under California’s Joint Powers Agreement Act.

Its primary functions are to represent its member agencies both on federal and state policy and on regulatory and political matters. We currently serve 32 public water agencies, and our governing body consists of the following 15 member agencies: Arvin-Edison Water Storage District, Chowchilla Water District, the City of Fresno, Fresno Irrigation District, Hills Valley Irrigation District, Kaweah Delta Water Conservation District, Kern-Tulare Water District, Lindmore Irrigation District, Lindsay-Strathmore Irrigation District, Madera Irrigation District, Orange Cove Irrigation District, Porterville Irrigation District, Saucelito Irrigation District, Terra Bella Irrigation District, and Tulare Irrigation District.

Kris Polly: Is the water you’re delivering used mainly for agricultural purposes?

Jason Phillips: The vast majority of it is, although the City of Fresno is one of the Friant contractors and one of our members. I would also point out that most of the San Joaquin Valley communities rely in large part on groundwater. The Friant Division, as a conjunctive-use project, helps keep those municipal water supplies sustainable by providing surface water for aquifer recharge and storage.

Kris Polly: Please tell us about the work that is being done to repair the Friant-Kern Canal.

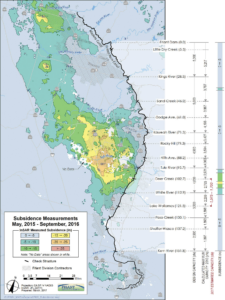

Jason Phillips: The Friant-Kern Canal is a 152-mile, gravity-fed canal. At the very top of the canal, where it comes out of the Millerton Reservoir, its capacity is 5,000 cubic feet per second (cfs); its capacity gradually diminishes, by design, to 2,500 cfs just south of Bakersfield. Since the beginning of the project, there has been an issue with ground subsidence throughout the entire valley. Over time, the ground slowly compacts, in part because of groundwater pumping and in part as a natural phenomenon.

However, some areas in the valley and along the canal subside faster than other areas. Given that the Friant-Kern Canal is an all-gravity-fed system, in those areas that are subsiding more quickly, it loses its capacity to move water at the rate it was designed to. Right about in the middle of the 152-mile canal, there’s a 20–30 mile stretch that is subsiding at a significantly faster rate than the rest of the system—about 1 inch per month. There are a lot of reasons for that, not all of which we have identified yet. It is largely caused by groundwater pumping, but the extent and geographic reach of that pumping are still being investigated.

I’ve often heard people say that the farmers in the Friant Division overpumped and sank their canal, and now they’re trying to find funding from the federal and state governments to bail them out. Actually, we’re almost certain that most if not all the groundwater pumping that’s causing the severe subsidence is occurring outside Friant Division lands. The lands that have contracts to receive water from Millerton Lake have reduced their overdraft and been more stable—that’s part of what the Friant Division was established to do. The impacts to the infrastructure are almost entirely caused by folks outside our division who receive little or no surface water.

The result of that subsidence is that that stretch of 4,000 cfs it is designed to convey. The effect of that, as you can imagine, is that when farmers downstream of that point need surface water, we are unable to convey it to them. Around 330,000 acres of land are affected. In some years, parts of that area receive less than half of what might be available to them that year from Millerton Lake under their Friant Division contracts. In wetter years, when there is flooding, the Friant-Kern Canal is used to convey flood flows and route them to designed groundwater recharge basins. The subsidence issue means that the canal has less capacity for this, too.

The result of that subsidence is that that stretch of 4,000 cfs it is designed to convey. The effect of that, as you can imagine, is that when farmers downstream of that point need surface water, we are unable to convey it to them. Around 330,000 acres of land are affected. In some years, parts of that area receive less than half of what might be available to them that year from Millerton Lake under their Friant Division contracts. In wetter years, when there is flooding, the Friant-Kern Canal is used to convey flood flows and route them to designed groundwater recharge basins. The subsidence issue means that the canal has less capacity for this, too.

In total, we estimate that 100,000–300,000 acre-feet of water—less in dry years and more in wet years—is not being delivered via the canal because of this capacity issue every year. The result, of course, is that 100,000–300,000 acre-feet more water is being pumped out of the ground every year instead, which is making the subsidence problem worse. More groundwater pumping, more subsidence. You can imagine that fixing this issue has risen to the top of our priority list.

Kris Polly: How do you solve that problem? Do you need to raise that section of the canal?

Jason Phillips: There are several alternatives. The easy way, if you will, is to raise the banks of the canal and the concrete liners within the canal by a certain amount. To do that, you’d have to increase the entire footprint of both canal banks.

Another option is to install a pump station near the bottom point of the subsidence area in order to move the water through more quickly. That does not appear to be a feasible option at this point.

A third option is not to enlarge the current canal but to construct a parallel canal. That could involve either constructing a completely new canal—an offshoot of the current canal that would route around and come back into it downstream—or using one of the existing canal banks as the bank of a new parallel canal, which would mean constructing just one new bank for 30–40 miles.

Without knowing the specifics of the project, an engineer would probably say that raising the banks of the existing canal is the most obvious solution. The reason we are considering a parallel canal is that along with these 30–40 miles of canal, existing county roads and bridges span our canal and have miles of approach roads. It is not easy to raise those bridges. Raising the canal banks and liners would require removing those bridges and rebuilding them. Building a parallel canal system would not. The analysis of these options is ongoing, and a report to the Friant Water Authority board on the final options is due in April.

Kris Polly: Please tell us about the alternative canal’s capacity and length.

Jason Phillips: The alternative canal would run parallel to the existing canal for a distance of approximately 30 miles and would have a capacity of 3,000–4,000 cfs.

Kris Polly: What are the complications of repairing or altering a canal that is currently in use? Do you foresee having to stop the flow of water entirely at any point?

Jason Phillips: What we will likely have to do—and this is something the designers will have to include in their construction plans—is to extend the construction over multiple years so that we can take advantage of times when there is little flow in the canal, like the winter. We do not want to disrupt deliveries. We almost never dewater the canal, because we have a lot of citrus in this area, and in the winter when a lot of other crops need water, temperatures in the San Joaquin Valley go down to freezing, and citrus growers need water to protect their crop. Only once every 3 years do we dewater the canal for inspection, sealing, and the removal of silt. That happens to be coming up in a year, and we will probably use as much of that period as possible, but it is only 3 months. If a parallel canal design were selected, this might also reduce impacts to water deliveries during construction, as the existing canal could potentially still be used during the construction process.

Kris Polly: Would you tell us about the challenges of funding major infrastructure projects?

Jason Phillips: In California in particular, agriculture is criticized for receiving subsidies from the federal government, but in this case it is hard to secure financing at all, to say no to bring it back to its design capacity would require $350 million or more; alternatives that would only restore part of the design capacity are in the $200 million range. Figuring out how to finance or fund that is quite challenging. We could possibly work through the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, through the U.S. Department of Agriculture, or through the Farm Bill.

As with many Reclamation facilities operated by local agencies, the title to the Friant-Kern Canal is still held by the United States. Even though the Friant Division’s 32 long-term contractors have a contract with Reclamation to receive water and have repaid the costs of the Friant-Kern Canal and related facilities, Reclamation still owns the canal itself. The federal government prefers to lend money for infrastructure projects to the owner of the facility in question, but in this case, the owner is itself, which complicates matters.

Historically, extraordinary maintenance on Reclamation projects would be funded by appropriations. If a large repair were needed, Congress would appropriate the money and we would enter into a contract to repay it. That would be fine with us, but getting funding in the budget in the climate of the last decade has been nearly impossible. Maybe a $1–2 million project is workable, but something on the magnitude of hundreds of millions of dollars is very unlikely. Aside from the 2013 stimulus package, federal infrastructure funding has been scarce.

That leaves us to look at local at local financing. We expect to run into similar issues: It’s not Friant Water Authority’s facility, and lenders prefer to lend money to the owner of the facility.

In 2018, California voters put an initiative called Proposition 3 on the ballot. It was essentially a $9 billion water bond and included $750 million for conveyance infrastructure in the San Joaquin Valley. That would have funded the Friant-Kern Canal repairs, any capacity issues with the Madera Canal, and potentially other canal repairs in the valley also. Unfortunately, it was defeated in the November election by less than 1 percent. Nevertheless, water bonds that can be passed by the voters could be a way to finance larger infrastructure projects in the future.

Kris Polly: Will your dams require maintenance as well?

Jason Phillips: It’s not currently on our radar, but it is true that Friant Dam is now 70 years old and at some point will require major infrastructure repairs. As in much of the West, our infrastructure was put into place 50, 75, or in some cases 100 years ago. We’ve been surviving with that gradually aging infrastructure minus what has been taken away through regulations, permitting, and measures like the Endangered Species Act. There are a whole series of new facilities and projects that have been proposed in California, but again, it is not clear where the money will come from to build them. This highlights the need for water users in the West to work with Congress, the president, and the administration to come up with a financing proposal that will allow large infrastructure projects to move forward; we can enter into whatever contracts are necessary to repay those costs.

Kris Polly: Based on your experience over the last few years, what advice would you have for other water authorities facing similar large-scale infrastructure projects?

Jason Phillips: My advice is to look strategically at the large infrastructure expenses you may have in the next 10–20 years and to work with your board of directors to finance them in advance. You want to have a capital fund. That’s hard. You have to collect money in advance. That’s not something people like to do—they’d rather keep the money invested. Alternately, you should put time into working with Congress to figure out how those larger infrastructure repairs will be funded.

In my experience at Klamath, at Friant, and in other parts of the Central Valley Project, water users, contractors, and farmers don’t worry about federal infrastructure, thinking that when it comes time to repair it, the Bureau of Reclamation will fund it. Other than a few examples like stimulus funding, that has not been the case.

When I started working with Friant in 2016, we had just had two of the worst droughts on record, back to back. There had been zero water supply allocation to Friant for the first time ever. There wasn’t much water running in the Friant-Kern Canal, and groundwater was being pumped heavily. We were not aware at the time how fast the subsidence was accelerating because of the pumping. We talked about the canal’s capacity issues, but that was not a priority. It was not until later in the year, when we started running more water in the canal, that we realized how much capacity it had lost in just a few years. Large infrastructure repair projects are difficult to predict. It is important to plan for potential repairs in advance.

Kris Polly: Looking at the long term, what is your vision for Friant?

Jason Phillips: At Friant, we and our board of directors focus a lot on strategic planning and short- and long-term goals. Our top priority is to ensure that we have the right expertise and executive team and legal team to protect Friant’s water rights and supplies. Over the past 10 years, those have not been in place as solidly as they should have been to weather the challenges we’ve faced more recently, some of which the Friant contractors were facing for the first time ever.

Second, we want a sustainable San Joaquin water supply—that includes our neighbors as well. Our supply of surface water plus sustainable groundwater must equal demand so that we don’t have an overdraft issue or future subsidence. We estimate that just in the San Joaquin Valley an average of 3 million acre-feet a year is being used in excess of the available supply—that means it’s being overdrafted from the groundwater. Our vision looking forward is to have the infrastructure and operational changes in place to ensure a long-term balance of supply and demand.

This year, we and our partners in the valley are preparing what we call a San Joaquin Valley blueprint, which will put forward what infrastructure and operation changes are going to be necessary and, quite possibly, how much land will need to be retired in order to reach that balance of supply and demand. That’s likely to include larger canals in addition to the Friant-Kern, new surface storage, new groundwater storage, and probably some operational changes as well.

Jason Phillips is the chief executive officer of Friant Water Authority. He can be contacted at jphillips@friantwater.org.