Oroville-Tonasket Irrigation District (OTID), located in north-central Washington State, enjoys senior water supplies from its sources in Lake Osoyoos and the Okanagan River. However, the region has undergone droughts in recent years, resulting in curtailment for junior water right holders. In order to make use of the water available to it and to help those without a reliable water supply, OTID has set up a water bank under which it can first protect, then lease a portion of its unused water to interested customers in the Okanogan River basin and downstream along the mainstem Columbia River. In the short term, the water will be leased to help offset the district’s ever-increasing costs, including those of future power obligations and deferred maintenance, resulting in lower property assessments and thus helping growers remain competitive in today’s agricultural market. In the long term, the water will be protected from relinquishment and kept available to support future farm expansion, consistent with the strong agricultural values of the local community.

In this interview, OTID Secretary-Manager Jay O’Brien speaks with Irrigation Leader about the inspiration for the district’s water banking system, how it works, and how the same concept can benefit other irrigation districts across the region.

Irrigation Leader: Please tell us about your background and how you came to be in your current position.

Jay O’Brien: I have been working for OTID since 1983. I started out in the maintenance department and worked my way up. In 2013, I accepted the secretary-manager position.

Irrigation Leader: Please tell us about the district’s history and current services.

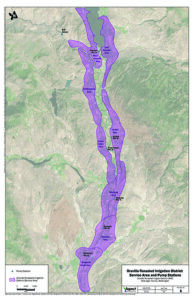

Jay O’Brien: OTID was born in 1916. In the mid-1980s, the Bureau of Reclamation updated the system, and we now have eight pumping stations located up and down the Okanagan Valley, from the Canadian border to a point 10 miles south of Tonasket, Washington. We irrigate about 10,000 acres and have about 1,500 customers. We have a totally pressurized system with no open canals, flumes, or ditches. The primary crops in our area are apples, cherries, pears, and alfalfa hay. In addition, a small portion of our service area is residential.

Irrigation Leader: What are the district’s current top issues?

Jay O’Brien: Maintenance and upgrades to our facilities. Our facilities are more than 30 years old now, and we are finding that pipelines need to be replaced and the pumping stations need a significant amount of work. We are finding it difficult to integrate 1980s technology with present-day technology.

Irrigation Leader: What are the district’s challenges when it comes to water supply?

Jay O’Brien: We are pretty fortunate with our water supply most years. We border with Canada and work closely with the International Joint Commission. We are obligated to create storage and maintain lake levels on Lake Osoyoos, a transboundary waterway. The International Joint Commission dictates flows and lake levels and provides the district with a curve to follow. The lake has a dam on it called Zosel Dam, which is owned by the Washington State Department of Ecology. OTID is under contract with Ecology to operate and maintain that dam in accordance with the guidelines of the International Joint Commission. Our water supply primarily comes down the Okanagan River, with supplemental supply from the Similkameen River.

Irrigation Leader: Would you explain what the basic idea of water banking is and why a district might want to do it?

Jay O’Brien: In order to address that, we need to talk about our state’s certified water rights examiner (CWRE) process. In 2013, when I became the secretary-manager of the district, I was told that our water rights had never been certified after a past change in points of diversion. To get those water rights certified, we had to go through a CWRE process, which is essentially a detailed review of historic irrigation practices and water use. We started that in July 2015 and finished in 2017, working with Aspect Consulting, LLC, a local water right consulting firm, and were approved by Ecology.

In Washington State, we have a use-it-or-lose-it law—if you don’t use your water or trust it for 5 consecutive years without sufficient cause, it can be relinquished. We learned from our CWRE process that we were not using all our water, primarily due to agricultural land fallowing and urbanization. Our first priority was to identify a way of protecting our unused water from relinquishment and our second was to find a method of offsetting future costs for the district and our growers. We landed on creating a regional water bank. We found that the district was regularly leaving approximately 7,500 acre-feet of water per year unused. We created a water bank and put that water in trust. Now we have water to lease downstream from the Canadian border all the way to the Pacific Ocean.

Water banking is a relatively new concept in Washington State. From our perspective, Ecology has done a good job of explaining to water purveyors like us what it is and how to set it up. All this results in our clients keeping water that they otherwise might have lost.

Irrigation Leader: What exactly does it mean that the water is put in a trust? Is it literally banked in a reservoir, or is it just notionally reserved for you?

Jay O’Brien: The banking is done mainly on paper through an agreement with Ecology known as a trust water agreement. By putting the water in the state’s Trust Water Right Program, we protect it from relinquishment under that use-it-or-lose-it law I mentioned. We can then debit that water bank when we find folks downstream who would like us to offset or mitigate their proposed water use through a long-term lease or water service agreement. This will likely be done by getting a new mitigated water right permit from Ecology. The permit will authorize the new use, but the effects of that use will be mitigated by the bank water. In order to provide long-term relinquishment protection, it is important that the district’s water is never taken out of the bank.

Irrigation Leader: Do you have any current customers for your water banking program?

Jay O’Brien: Not right now, but we are in negotiations with several interested parties. In addition, in coordination with Ecology, we plan on providing mitigation for future droughts. So far, 2020 is looking pretty dry, with limited snowpack in the mountains. It is important to the district to be a good neighbor and to work with Ecology to offset drought-year impacts in the Okanogan River basin and the downstream Columbia River basin.

Irrigation Leader: How much money do you expect to make?

Jay O’Brien: That would be determined by the length and content of the contracts. Water values are all over the place right now.

Irrigation Leader: In drought years when you really need the water, could water banking prove to be a disadvantage? For example, could you have already sold water that you then end up needing?

Jay O’Brien: That is unlikely. We have years and years of data to work from and are pretty comfortable with the amount we have decided to make available for long-term lease. For instance, in 2019, the Okanagan Valley was in a severe drought. We were able to do a short-term, 1-year lease to a grower downstream to alleviate drought-related impacts. This last year was really the catalyst to kick off the water bank: We worked closely with Ecology to offer the water bank to all junior water users that were curtailed due to drought conditions.

Irrigation Leader: Was your water banking program inspired by programs that other districts had established?

Jay O’Brien: I’m not aware of any other districts in our area that have a water bank. We were one of the first, at least in the upper Columbia River basin. I believe there have been a couple of similar transfers in the lower basin.

Irrigation Leader: The water banking system was supported and promoted by the state, correct?

Jay O’Brien: Yes. We worked closely with Ecology. As mentioned, we suffered a pretty significant drought in Okanogan County in 2019. As we were thinking about doing this and slowly working through the water banking requirements, Ecology saw that this was desperately needed during the drought to offset junior water use and help support instream flows. Together, Ecology, OTID, and our consultant got the entire permitting process completely done in 3 months, which is incredible. We also coordinated on an open house presentation, a drought-year mailer, and a website, which you can find at www.aspectconsulting.com/otidwaterbank.

Irrigation Leader: Does an irrigation district need to have certain characteristics for water banking to be an appropriate option?

Jay O’Brien: Before a district moves forward with water banking, it needs to do a tremendous amount of research into what its usage has been for the past few decades in order to make sure it has water available. It also requires a district to recognize a reduction in water use and/or identify exemptions to relinquishment within 5 years. We were lucky to have senior water right certificates and an overlapping permit that is not subject to relinquishment. If a district meets all those criteria, and all the permitting stars align, water banking is a great way to protect an unused water right and perhaps create a little bit of long-term revenue. But I want to stress that our primary goal was to protect the unused water so that when local agricultural markets return, the district will be able to provide reliable water supply. Supporting agriculture is a strong local value, and it is one that is shared by the district.

Irrigation Leader: Do you have any advice for districts that are embarking on the creation of a water banking program?

Jay O’Brien: Find a really good consultant to help you through the process. It is also important to coordinate with Ecology or the equivalent agency in another state throughout the process and to demonstrate that the overall project benefits the public. This includes being transparent and giving the agency plenty of review time for all technical work products ahead of mandatory review periods.

Irrigation Leader: What is your message to Congress and to the Washington State Legislature?

Jay O’Brien: Water banking has received of lot of attention in the press lately, both good and bad. From my perspective, the state’s water banking system generally works pretty well, and it is important not to overcorrect because of one or two bad examples described in the press. Do your best to streamline the processes by which water is protected and moved around the state to address current and future agricultural needs.

Irrigation Leader: What is your vision for the future of your water banking program?

Jay O’Brien: The vision for the future of our water banking program is to provide water supply and create the revenue necessary to secure the future needs of the district. As far as power use goes, we want to upgrade the system as needed to address the natural aging of the system and eventually to provide reliable water supplies at a lower price.

Jay O’Brien is the secretary-manager of the Oroville-Tonasket Irrigation District. He can be contacted at otidjay@nvinet.com or (509) 476-3696, extension 3.